Nearly a century ago, London’s iconic Battersea Power Station (pictured on Pink Floyd’s Animals album cover) fired up its coal boilers to provide electricity to the growing city. To avoid the smoke and sulfur dioxide emissions common to Welsh coal, they installed wet scrubbers, which were very effective at reducing air pollutants. The problem was they transferred the pollution to the Thames River. They didn’t eliminate the emissions, but instead created a different form. This is the concept we now call the energy penalty paradox.

Today, facilities moving into hydrogen production face the same paradox in a new context. Finding ways to reduce overall emissions is the topic of my article in the Winter 2023 issue of Global Hydrogen Review, titled Solving the Paradox. The challenge in this case is finding ways to manufacture hydrogen in large volumes without emitting carbon dioxide.

The underlying objective is positive: provide hydrogen to support low-carbon and net-neutral fuels. The paradox is that using natural gas as the feedstock emits carbon dioxide. If the process creates “gray” hydrogen, as most hydrogen production does, we simply move the carbon dioxide emissions to another place in the process. Fortunately, as the article points out, this doesn’t have to be the case.

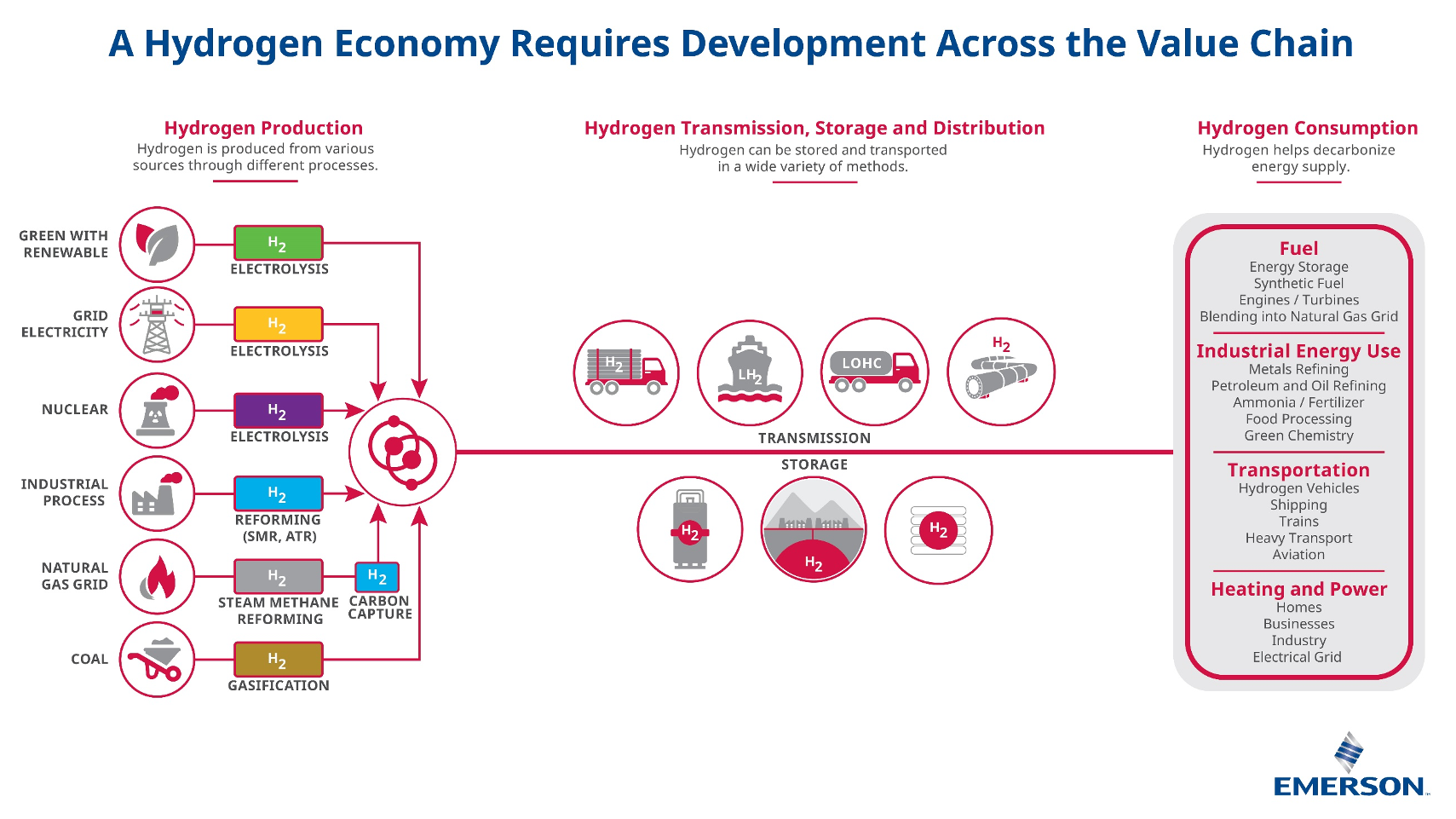

The situation is more subtle for hydrogen producers these days than for Battersea, but it is possibly more difficult to solve. Natural gas as feedstock is still necessary to manufacture the volume needed by all applications:

The best approaches today recognize that production from natural gas is still irreplaceable, but its climate effects must be mitigated. There is a hopeful sign: the hydrogen production method in these situations can be changed from “gray” to “blue” without disrupting capacity. In the short-term, this development promises to reduce emissions far faster than all the other processes since it has the potential to affect the bulk of existing hydrogen production.

The objective is twofold: make the reforming process, which turns natural gas into hydrogen, more efficient, but also improve the process that captures and stores carbon dioxide. Reforming processes consume a lot of energy themselves, usually by burning natural gas. Let’s start there:

There are two reforming approaches that dominate the industry today. The first is steam methane reforming (SMR). The second option is autothermal reforming (ATR), which produces syngas, a mix of hydrogen, carbon monoxide, and carbon dioxide. Both processes consume large amounts of natural gas a fuel, so controlling combustion in this part of the process has a direct effect on overall energy consumption.

The article goes into greater depth on how Emerson can help reduce overall energy consumption related to hydrogen production, thereby mitigating the effects of the energy penalty paradox. For example, Emerson’s Micro Motion Coriolis Mass Flow Meters help balance fuel and energy flow. When this is combined with oxygen analysis for flue gas using Emerson’s oxygen analyzers, the amount of natural gas necessary to produce a volume of hydrogen is minimized.

Emerson instrumentation can also make SMR and ATR processes more efficient overall. Taken together, the effect can be significant.

Automation technologies are designed to optimize reforming and carbon capture units by delivering advanced control, increased process visibility, and actionable information for improved decision making, all of which are necessary to meet global net-zero goals and realize a sustainable economy for future generations.

For more information, visit Emerson’s Decarbonized Hydrogen pages at Emerson.com. You can also connect and interact with other engineers in the Chemical Processing Groups at the Emerson Exchange 365 community.