At the 2019 Ovation Users’ Group conference, Emerson Jason King provided an update on Ovation DCS solutions for cooling towers. Jason opened explaining that $450,000 USD can be saved using automated cooling tower monitoring and optimization solutions.

At the 2019 Ovation Users’ Group conference, Emerson Jason King provided an update on Ovation DCS solutions for cooling towers. Jason opened explaining that $450,000 USD can be saved using automated cooling tower monitoring and optimization solutions.

Several challenges exist for cooling towers in the power generation industry. Cooling towers are used to condense the steam exiting the steam turbine. This helps complete the flow of steam through the turbine. It is important to condense the steam as it exits the turbine because this action creates a vacuum in the condenser which helps the steam do the maximum amount of work in the turbine.

For this reason, condenser temperature is critical to steam turbine performance, which means the components of the cooling tower are critical to steam turbine performance. Circulating pumps send the water from the cooling tower through the condenser, so if they aren’t functioning, the steam turbine is essentially useless. The fans in the cooling towers are critical to full cooling performance of the circulating water, although not all cooling tower cells are needed 100% of the time. A variety of load, influent cooling water temperature, ambient temperature & relative humidity combinations require maximum cooling tower performance in order to meet cooling demands.

Cooling towers are one of the top reasons for heat rate loss in a power plant. The status quo for the majority of cooling towers include: limited automation and/or manual control (fan speed, number of fans, number of pumps), unbalanced cell flows, unknown circulating water pump performance degradation, vibration switches for trips, occasional route-based vibration assessments, cell operation favoring certain fans over others, cooling tower cell freeze, and basin overflow due to valve issues and lack of level instruments.

These conditions lead to derated steam turbine output, pump wear, increased fuel usage in the boiler or gas turbines for a given load and can even mean reportable environmental events. The condenser vacuum, also know as turbine back pressure control, should be minimized by pulling sufficient vacuum by condensing the steam from the turbine. Too much vacuum though can waste energy. Typical operating practices include manual cell selection, speed settings, and circulating pump operation. These practices lead to mechanical wear on fans / gearboxes (from operators favoring certain fans over others, or simply being forced to guess which fan has the least amount of use and should therefore be started) and cooling the condensate more than is necessary,

Another example is the circulating water pumps that may have one speed, two speeds, or operate on variable frequency drives. With one or more cooling trains within your circulating water system, control of these water pumps may be manual or have some limited automation (for example: startups). Rarely do control systems show pump performance relative to their efficiency curves, nor do they attempt to operate the circulating water system such that pumps can operate as efficiently as possible. This may create potential for wasting energy, pump damage and shortened pump life, unplanned circulating water pump failure, and if that happens, significant steam turbine derates.

Many cooling towers have little to no monitoring systems. If they have any vibration monitoring, it is done on a quarterly or semi-annual basis as a portable route, and any protection from a catastrophic event is left to simplistic (and often unreliable) vibration switches that require frequent calibration and maintenance to perform their intended function when needed.

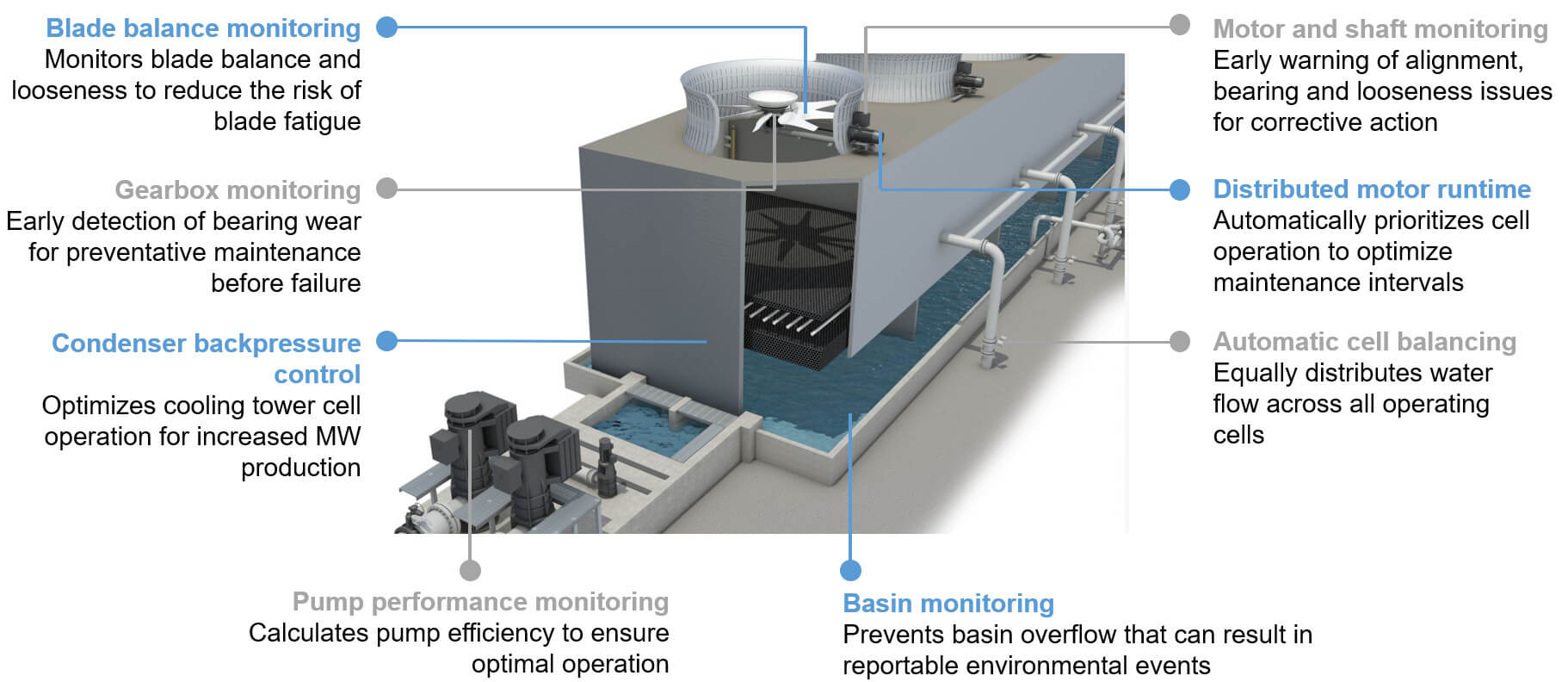

All of these issues can add up to the $450,000 savings that Jason opened with. Here are the many areas that solutions can be applied for more efficient cooling tower and turbine operations:

Visit the Integrated Migration Monitoring section on Emerson.com for more on the Cooling Tower and other solutions to improve operational performance.