Douglas Morris from Emerson’s Alternative Energy team comments on the recent announcement by the U.S. government to use the Defense Production Act to spur the development of advanced biofuels.

In the past year, the advanced biofuels industry has hit a bit of a rough patch as it attempted to bring its many promising technologies to demonstration or commercial scale. As with any new industry, the cost position of producing these fuels is typically high because there is no benefit of scale from proven commercial installations. As such, most of these companies require some form of grant or loan guarantee to mitigate the risk of constructing these facilities. The recent debt discussion in Washington DC has placed most of the funds previously set aside to help this industry on hold.

Enter the US Navy who, along with the other branches of the military, has been stating for years the need to diversify its fuel supply to be less reliant on traditional petroleum feedstocks. Ever hear of the Defense Production Act or DPA? It’s actually been around since 1950 and was created to help ensure that industrial resources are available to meet national security needs. The President, who has the power to enact the DPA, recently announced through his administration the availability of $510 million over the next three years to develop drop-in aviation and marine diesel biofuels. The government will be collecting information to evaluate possible technologies to consider until the end of September. Here’s a link to the Request for Information (or as the acronym-heavy military might say DPA RFI).

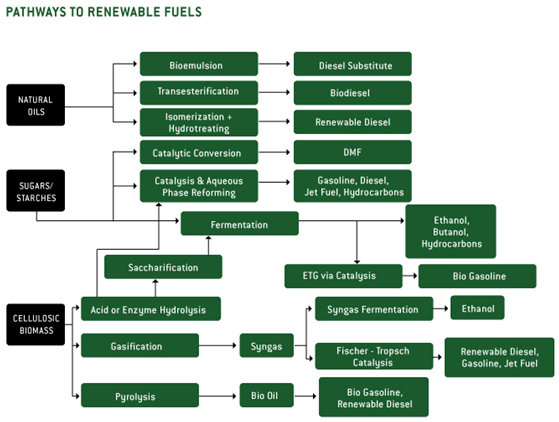

What does this mean for advanced biofuel companies? Well, this funding knocks out the possibility for many in the industry who produce Ethanol as an end product. It’s not that the government is against Ethanol, rather it’s because the military must pick fuel sources that require no changes to their engines or distribution infrastructure. In fact, these projects will be limited to those that can produce jet propellant, JP-5 (used by the Navy on aircraft carriers), JP-8 (used for non-carrier aircraft), or F-76 (military diesel) fuels.

From Advanced Biofuels Association, Michael McAdams, President

Other key considerations for these projects are first that the technology is capable of being scaled to commercial-sized plants and second that the technology can be deployed in Hawaii. As a former Navy guy, I’ll attest to the fact that easy access to fuel in Hawaii is a must for the Pacific fleet.One doesn’t need a crystal ball to guess which technologies will be in the running. They will most likely include algae, camelina, and other oil-based pathways. Regardless of the technologies chosen, this approach will give this industry a needed boost to commercialize development. In the end, we will all likely benefit as history shows that military programs, in time, pass their innovations on to everyone.