With vast shale gas reserves, will China move from coal-to-chemicals processes to gas-to-chemicals processes going forward? Emerson’s Douglas Morris, a member of the alternative energy industry team explores this question in today’s guest post.

We’ve had a number of posts where shale gas is discussed and this week is no different. An interesting article about a startup company was highlighted in the Wall Street Journal this week, which discussed a unique process for producing ethylene from natural gas.

The article, “A New Use for Shale Gas“, discusses the company Siluria Technologies and their lower temperature process for converting natural gas into ethylene. This company certainly has the potential to change the market if they can demonstrate this technology with their planned pilot facility.

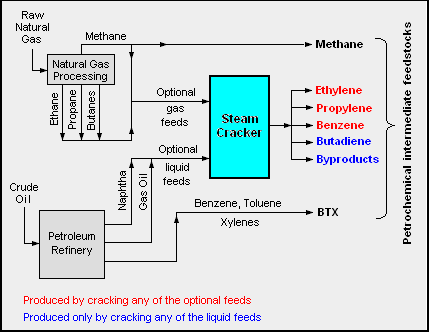

Olefins have lots of pathways, including methanol, refining gas, naptha, liquefied petroleum gas (LPG), and yes, natural gas.

Until recently, economics have pushed the process to use petroleum residues because of cost. The economics are changing and there are a number of large players (Dow, Shell, Total, Chevron) that are somewhere in the planning/construction process of building olefins plants that use natural gas. The Siluria process, with its lower cost, can certainly become a player if it turns out to be financially compelling, but what really intrigues me is how a low-cost natural gas to olefins pathway may impact the growing coal chemical market in China. China is moving the majority of its coal chemical program from plants producing primarily methanol to plants producing olefins, and ironically, substitute natural gas (SNG).

China has the third largest coal reserves in the world and is using this resource to produce both power and chemicals. (I’ve written before and discussed how China is leading the world in chemical production from coal). For shale gas, China has the world’s largest reserves.

This past year, the country has started some hydraulic fracturing (fracking) to release gas deposits. But, it is currently limited on how much it can produce because it does not have enough water to support fracking on a large scale. Large portions of their reserves are in the arid part of Central China. As far as coal chemical is concerned, the country finds itself also water limited for these plants.Looking into the future, though, if a process like Siluria’s or another low-cost olefin pathway is commercialized, China is ripe to take advantage because of its vast shale gas reserves. Will this make China move from a large coal to chemical industry to a gas to chemical industry instead?