The goal of the U.S. Renewable Fuel Standard is to increase the use of alternative fuels in the transportation fuels mix. Emerson’s Alan Novak, leader of the alternative energy industry team, looks at this law versus the realities of today’s energy demand.

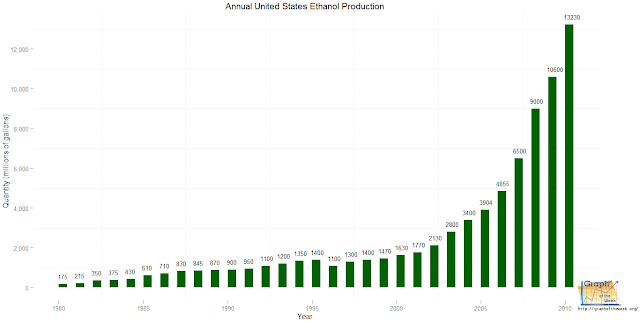

As discussed in a previous post, the Renewable Fuels Standard (RFS) and the Renewable Fuels Standard 2 (RFS2, technically the Energy Investment and Security Act of 2007) have been the primary drivers behind the dramatic growth in the US Renewable Fuels industry.

Current corn ethanol production (the dominant US renewable fuel):

While there have been periodic attempts to revisit the standard, most notably during the 20XX drought, there have rarely been serious discussions around outright repeal or modification of the volume mandates proscribed.

That appears to be changing.

The House Energy and Commerce Committee recently launched its first formal review of the RFS and is seeking comments on an RFS white paper currently posted on its site.

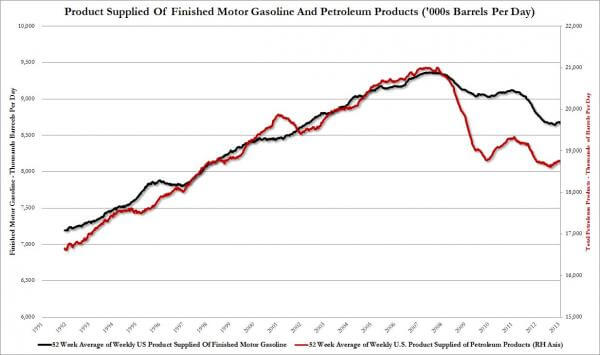

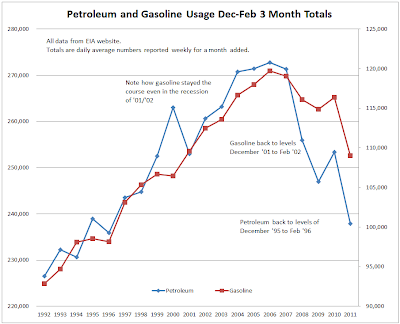

The greater interest in re-visiting the standard is driven by something few anticipated in 2007–the declining demand for gasoline in the US. Rather than the steady 1-3% increase in gasoline consumption that was expected in 2007, demand that year actually served as a high water market and consumption has been falling ever since.

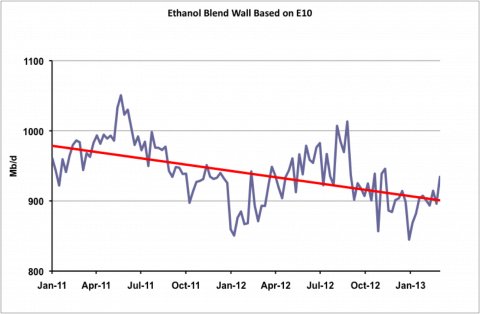

Since the maximum allowable ethanol blend for automobile fuel is currently 10 percent (85 percent ethanol-E85 is also available for flex fuel vehicles but its adoption has been slow), the available market for ethanol is set at 10 percent of current gasoline demand. This limit is the basis for something called the “blend wall”, the maximum amount of ethanol required to meet US fuel demand. Falling gasoline demand has resulted in a situation where the RFS mandated ethanol blend volume (900 M barrel/day) now exceeds market demand (895 M barrel/day as of March 2013).

So how do gasoline suppliers address this imbalance? Through the purchase of Renewable Identification Numbers (RINs), which are credits issued by producers or blenders of renewable fuels. As the blend wall approached, the cost of RINs has soared. RINs allow producers to meet the RFS mandates even if there is insufficient fuel demand.

If gasoline demand continues to decrease, the gap between available market and the RFS mandate will continue to increase resulting in increasing demand for RINs to offset the difference. Since producers purchase these credits, they directly impact the final consumer cost of gasoline.

What are the options to resolve this mismatch? Three options would be: lower the required blend volume; increase the available market (higher blend percentage); or tie the mandate to the actual underlying demand. Only time will tell which option is selected.